- Home

- Patrick Carman

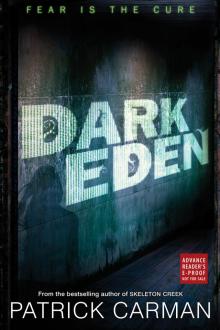

Dark Eden

Dark Eden Read online

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

Advance Reader’s e-proof

courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers

This is an advance reader’s e-proof made from digital files of the uncorrected proofs. Readers are reminded that changes may be made prior to publication, including to the type, design, layout, or content, that are not reflected in this e-proof, and that this e-pub may not reflect the final edition. Any material to be quoted or excerpted in a review should be checked against the final published edition. Dates, prices, and manufacturing details are subject to change or cancellation without notice.

DARK

EDEN

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

DARK EDEN

PATRICK CARMAN

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

ARRIVAL

THE DAYS OF OUR CAPTIVITY

BEN

KATE

ALEX and CONNOR

MARISA

WILL

AVERY

RAINSFORD

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

This book is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents, and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Dark Eden

Copyright © 2011 by Patrick Carman

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information address Avon Books, an Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-06-200970-8

T11 12 13 14 15 XXXXXX 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

For Cassie and Sierra Keep the lights on.

Our Location (give or take twenty miles)

[map of Fort Eden and area to come.]

DARK

EDEN

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

ARRIVAL

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

.....................................................................

EDEN 1

Why are you hiding in this room all alone?

There will be no shortage of questions about Fort Eden, the seven, Rainsford, Davis, Mrs. Goring, the program. But the first question, the one that will set all things in motion, will be a simple one. It will be asked when they find me.

We asked you a question, Will. Why are you hiding in this room all alone?

I’ve thought about how I will answer. I won’t like being cornered. I won’t like seeing the door blocked by a person I will be forced to speak with. Better I have the answer memorized so they’ll let me out into the woods where I can run.

Because I knew.

That’s what I’ll say when they ask.

I knew, and I was afraid.

WILLIAM BESTING, S167

DR. CYNTHIA STEVENS

6.12.2010

There are more like you. You’re not the only one, Will.

How do you mean, more like me?

You’re not the only one who’s afraid. Lots of people your age are afraid of things. The world can feel scary when you’re fifteen. But for some people, like you, certain things are much scarier than they should be. You know this. We’ve talked about it. But you don’t have to be alone; there are others like you.

Why are you telling me this?

I was looking at my notes before you came in today. We’ve been meeting a long time. Too long, Will.

Wait, what?

Do you trust me, Will? Really trust me?

I guess so. Sure.

Then I’ll tell you the truth. I can’t help you. I want to, but I can’t. And there are others like you, six to be exact. Six others I can’t help. Six others who are afraid like you are afraid. And there’s a place I want you all to go.

You mean me and six people I’ve never met? How old are they?

Same age as you.

I’m not doing that. You can’t make me.

Your parents want you to go. I’ve already asked them. I think they might be growing tired of my lack of progress. One hundred and sixty-seven sessions, Will. Over two years. Don’t you see? I can’t help you. But I think someone else can.

Where’s this place I’m not going to, and who are these people I won’t be meeting when I don’t get there?

After that the screen on her phone lit up, and she glanced away from me as I watched. Dr. Stevens was a tall, lean woman of about forty. She was blond and pretty and wore smart, rimmed glasses, all of which were a constant distraction. She had a crooked front tooth, which should have marred an otherwise beautiful face, but it was disarming and natural. In my opinion it was the thing that made the whole package, the ribbon.

Excusing herself, she left the room, which was on the third floor of a converted row house that she shared with three other counselors. She left the door a few inches ajar; and I knew when her foot touched the fourth step down, because the stair creaked loudly enough for me to hear from inside the room. Far away, at the bottom of the stairs, I heard the soft sound of a door closing. She’d gone outside onto the front porch to call someone, or so it seemed. The quiet hum of voices drifted in from another room like a cat purring down a dark alley, and I got up from my chair.

We’d been meeting for so long, it was as if Dr. Stevens was my aunt or a much older sister. Sometimes she’d eat lunch while we met; other times she’d take a break and go to the bathroom or to the kitchen downstairs, leaving me to rummage through her things as I waited for the sound of the fourth step on the stairs.

She should have known better then to leave me alone. She shouldn’t have scared me like she did. Looking through her things had become a bad habit, like shoplifting a newspaper you weren’t even going to read and then finding you were taking something that wasn’t yours every time you walked into a store. That’s the way it is with secrets. They pile one on top of the other until it’s like a house of cards that requires a lot of work to maintain.

It’s been a long time since I took my first file from Dr. Stevens’s office. If I was building a house of cards, I’d be on my second deck by now. Looking back, there are a few sessions that stick in my memory more completely than all the others.

SESSION NUMBER 12

I thought Dr. Stevens might be reading my future in the tea leaves at the bottom of her cup, but she was only thirsty for more caffeine

, fuel for another half hour with Will Besting. A few keystrokes on her laptop and down the stairs she went, leaving me alone in the room for the first time. I got up from my chair, sat in hers, and looked at the screen of her laptop.

Her computer was locked, but that was easily undone. Dr. Stevens was careless in her keystrokes, a password much too short and too easy for searching eyes like mine. I could only catch her fingers on the first two strokes—c and the a—then the dart of her skinny index finger up to the keys above. She punched four or five more keys with speed and precision as I pretended to look out the window, my head turned one way and my eyes another.

The password had started with c-a and probably continued up there, on that top row, with her long white pointing finger: a t.

cat

I won’t lie; it was a thrill from the start, sitting in her chair with my fingers flying over the keys, trying to unlock her secrets. Secrets about me. About her.

catplay. catonroof. cathairball. catcatcat. catfood

The fourth step creaked, and I flew back into my own chair, gripping the wooden arms as Dr. Stevens reentered the room from behind me, her cup filled once more.

A half hour later as we said our farewell, my eye caught a line of books sitting on a shelf. There were four, but only one mattered: the one with a blue background and a cat on the front tipping its striped hat and smiling happily.

catinhat

A password I would come to know all too well.

SESSION NUMBER 19

I found my own folder, filled with audio transcripts. I’d known she was recording all of our sessions—even consented to it—but somehow seeing them there, all stacked up with dates on them, bothered me. It was as if she’d dug deep into my soul and yanked out the secret parts, then stored them like little coffins in a meat locker.

I discovered that my parents had betrayed me, too. For years I’d kept an audio diary of my own that dated all the way back to 2005. I was just a nine-year-old kid when I started, back when I loved to hear my own voice. Dr. Stevens had them all, including the ones where the trouble started.

SESSION NUMBER 31

I kept a chain around my neck after that, from which a silver St. Christopher’s medallion hung loosely under my shirt. The medallion was oval shaped—as thick as three sticks of gum—and if I pulled St. Christopher apart at the middle, he was something more useful. St. Christopher’s detached lower half was a flash drive, with space enough on it for many, many audio files.

catinhat

I touched the folder marked WILL BESTING, dragged it across the screen, and fed its contents into St. Christopher.

SESSION NUMBER 167

And so it was that whenever Dr. Stevens left the room with her phone in hand, I took something more, something I’d told myself I wouldn’t touch.

catinhat

I was in, my heart racing as it always did when I sat in her chair. I’d long since found my way around. I knew where all the patient audio files were. I could have listened to them at my leisure while lying on my bed at home eating jelly beans. But I hadn’t done that, not ever. I’d only ever taken my own things, because I’d felt then as I do now that they belonged chiefly to me, not to my parents or to Dr. Stevens.

There had always been a certain folder I’d wanted to explore. It was a folder that enticed me like the smell of buttery popcorn from our kitchen, reaching all the way down the hall and into my room.

THE 7

All the other folders had patient names or dates or benign categories attached to them. But this one—THE 7—what did it mean? She was a doctor, so it had to be seven patients. But why these seven? And why put their information in a folder by themselves, apart from all the others?

What had she said to me? I can’t help you. I want to, but I can’t. And there are others like you, six to be exact. Six others I can’t help. Six others who are afraid like you are afraid. And there’s a place I want you all to go.

I pulled St. Christopher apart at the middle. The drive free in my hand, I carefully inserted it into the USB port. The saint’s silver legs stuck straight out, making it look as if his head was inside Dr. Stevens’s computer, looking around for the 7, peering inside folders as he searched for what was mine.

I didn’t look inside just then; I simply dragged the folder over to the drive and watched as dozens of audio files copied into my possession.

I didn’t have to open the folder to know what I would find inside. I’d find my own name there. There were six others, and there was me.

I was one of the 7.

During the months that followed, Dr. Stevens and my parents tried to convince me that a week away from home was going to finally put my problem behind me. No one was calling the opportunity by its true name; instead they used the gentle hook of camp, as in summer camp, with a bunch of my pals riding in canoes and shooting arrows. The arrows and the canoes and the pals, I knew, were not to be. I understood what I was really being asked to do and what they all thought of me. They imagined I was incurable. They were pulling out the stops, going for broke.

“We’re looking for a breakthrough,” my dad said, his eyes pleading for a yes and the tone in his voice suggesting that I was ten and the two of us were chums. “Dr. Stevens thinks it will work, and we believe her. Just give it a shot.”

“Tell Will what she told us,” my mom added, touching my dad’s hand. “About this Rainsford fellow.”

“The only reason you’re even going is because the guy trained Dr. Stevens like twenty years ago. He’s some sort of genius. There’s a program he offers right outside of LA, very exclusive, very expensive. And she’s getting you in for practically nothing.”

“You see? We only want the best for you,” my mother added.

“Why can’t I go alone?” I asked.

“Because it’s a bunch of people working on this stuff together,” my dad insisted. “It’s not like seeing Dr. Stevens. It’s different is all.”

“You mean group therapy, like for crazy people.”

My dad threw his hands up and walked into the kitchen, but then he turned back and put his palms on the dining-room table where my mom and I sat.

“Just think about it, okay? We think it’s the best thing for you.”

Weeks went by in which I pleaded with my parents, but there came a moment five days before my departure when I realized they weren’t going to let me stay home. I knew this primarily because of my younger brother, Keith, who was startlingly accurate about predicting my parent’s intentions.

“You’re going; it’s already decided,” he told me. We were sitting on the floor in my room playing Berzerk on an old Atari 2600 that I’d gotten on eBay. He was wearing the same lime green baseball cap he always wore, pulled down low so his hair spiked up around the sides of his ears. The game, like so many from that era, made some of the most excellent robot sounds I’d ever heard. They were the kinds of sounds that got stuck in my head and danced around until dawn. When the robots found you, they’d chase you around with a monotone warning: Intruder alert! Intruder alert! It sounded like an electronic voice speaking into a spinning fan.

My scores were so much higher than his that I felt sorry for him—my Achilles’ heel. Never feel sorry for a younger brother in a competitive situation because he’ll always get you in the end.

“You’re sure?” I asked, not taking my eyes off a 2D robot walking stupidly across the screen.

“They’ve got that look. It’s over.”

Keith was thirteen and gangly and popular. He was quiet and mysterious like me, but a much better athlete. One day I’m killing him at air hockey in the garage—a meaningless achievement—and the next thing I know, he’s wiping the basketball court with my face, which really mattered.

“Just go,” he said, standing up to leave but hanging back to observe a little longer, drinking in the gaming skills he’d later use to obliterate me. “It’s not gonna kill you.”

When I turned to look at him he was gone, like a gho

st who’d delivered a crummy message only to disappear when I needed him the most. Sometimes I felt as if Keith was the older brother, not me. I sat at my desk and stared out the window at the street below as my laptop whirled to life.

For the next three hours I listened to the voices of the seven—including my own—and played Berzerk, my mind melting into a sea of purple robots and bizarre fears I knew nothing about.

What she couldn’t have known as we sat next to each other in the backseat of a van heading out of LA was how well I already knew her.

Marisa Sorrento’s voice—like everyone else’s in the van that day—startled me when I heard it in person for the first time. I’d wondered what it would be like, connecting a voice I knew intimately with a real body and a real face. Marisa Sorrento, the one whose voice I’d liked the best, the one I was most drawn to.

“Can you believe our parents are making us do this?” she asked. Before I could answer, someone else broke in.

“It might be fun, like camp.” This voice I also knew. Alex Chow, whose parents had clearly sold the week to him in the same way it had been sold to me. Knowing what I knew about Alex, coupled with the fact that we were heading into the wilderness, I thought it was a miracle that he hadn’t thrown open the van door and hurled himself onto the pavement.

A conversation ensued in the rows ahead of me, and my attention drifted back to Marisa. She was Latina, which I had guessed because of her name; but if it hadn’t been for that, I might not have said so. Her voice, like her cinnamon-colored skin, was soft and almost too perfect. While I had been listening to her, I had felt that it was the voice of someone trying very hard to cover any sign of an accent. She lived with her mom and a sister, I knew, and there was some mystery surrounding the death of her dad several years back. Her eyes were dark brown pools that searched mine, waiting for a reply. What had she asked me again?

Eve of Destruction

Eve of Destruction Phantom File

Phantom File Ghost in the Machine

Ghost in the Machine The Land of Elyon #4: Stargazer

The Land of Elyon #4: Stargazer The Tenth City

The Tenth City The Dark Planet

The Dark Planet The Crossbones

The Crossbones Mr. Gedrick and Me

Mr. Gedrick and Me The Black Circle

The Black Circle Floors

Floors Beyond the Valley of Thorns

Beyond the Valley of Thorns Quake

Quake Tremor

Tremor Rivers of Fire

Rivers of Fire The House of Power

The House of Power Dark Eden

Dark Eden Into the Mist

Into the Mist Fizzopolis: The Trouble With Fuzzwonker Fizz

Fizzopolis: The Trouble With Fuzzwonker Fizz Pulse

Pulse 3 Below

3 Below The Dark Hills Divide

The Dark Hills Divide Skeleton Creek

Skeleton Creek The Raven

The Raven Thirteen Days to Midnight

Thirteen Days to Midnight Fizzopolis #2: Floozombies!

Fizzopolis #2: Floozombies! Rivers of Fire (Atherton, Book 2)

Rivers of Fire (Atherton, Book 2) Stargazer

Stargazer The Trouble with Fuzzwonker Fizz

The Trouble with Fuzzwonker Fizz Floors #3: The Field of Wacky Inventions

Floors #3: The Field of Wacky Inventions Floors #2: 3 Below

Floors #2: 3 Below Floors: Book 1

Floors: Book 1 Crossbones

Crossbones Floors:

Floors: Fizzopolis #2

Fizzopolis #2 The Black Circle - 39 Clues 05

The Black Circle - 39 Clues 05 Into The Mist (Land of Elyon)

Into The Mist (Land of Elyon)