- Home

- Patrick Carman

Into The Mist (Land of Elyon) Page 3

Into The Mist (Land of Elyon) Read online

Page 3

28

pulled from the earth flew over his head and tumbled down the hill behind us.

When Thomas sat up he was dazed, rubbing his head and looking all around for the object he'd found.

"It's there," I said, pointing down the hill. I could have beaten him to it, but it was he who had been determined to stay at it when I had wanted to walk away. I pulled my brother back up on his feet and followed him toward the object.

"What are you idiots up to now?"

It was Finch coming down without the dogs. He was sometimes like his mother in the way he sneaked quietly from place to place in order to surprise, a wicked habit with only one purpose: to catch someone doing something he or she shouldn't be doing. Lost in our struggle with the strap and the dead horse, we'd forgotten to keep a close eye on him. Finch was quite a bit older and bigger than we were, and he enjoyed pushing us down or punching us in the chest for no particular reason. His fists were clenched as he came, a sign that he was eager to inflict some abuse on both of us.

Finch sniffed the air.

"What's that stench?"

Thomas and I were standing down the hill from the place where we'd uncovered the remains of the

29

horse, but we hadn't yet reached the thing that we'd pulled free. Finch kept walking toward us until he stumbled and slid right into the place where we'd been digging. He sank into the mess we'd uncovered and looked down at his feet. Before he could throw up, he pitched forward and made a heaving sound, but nothing came out. Jumping out of the hole, he ran a few paces back toward the top of the hill, then looked back at us with a growing fury. When Thomas started to laugh, I elbowed him in the side. Finch was in no mood to be ridiculed.

"That's the last time you make a fool out of me!" he screamed. "Just you wait until tonight. We'll see who's so funny!"

I could see that what Finch really wanted to do was to come down the hill and beat the both of us senseless, but the smell was too much for him and his full stomach. He made for the top of the hill, no doubt to tell Madame Vickers of our mischief. My heart sank at the thought of what the rest of the day would bring.

"He thinks we did that on purpose," I said. "We may have accidentally pushed him a little too far this time."

I looked to where Thomas had been standing beside me, but he had moved off, already kneeling by the thing that had been attached to the leather

30

strap. I looked back toward Finch and saw that he was nearing the top of the hill, waving his arms at Madame Vickers.

"Roland, come quick!" shouted Thomas. I darted down the hill and crouched beside him. The strap we'd been pulling on was attached to a grimy old saddlebag with the name Mingleton branded onto it. Thomas had already opened up the bag and put his hand inside. I watched eagerly as he pulled out the one thing that lay hidden in Mingleton's saddlebag. It was a single piece of paper -- discolored, crumpled, and torn at the edges. But none of that mattered, for we both sat silent and stunned by the worn image and the words on the page before us. A symbol on the paper was something we'd seen before.

We drew our pant legs up and stared at our skinny legs. The symbol on the paper was that of a square and a teardrop put together as one, and the same marking was etched like a tiny birthmark at the top of both our knees. There were more markings on our skin -- many more -- but of this I will have to tell you later, for just now a bit of trouble had arrived in our midst.

"Give it to me this instant!" We turned our heads to find the bone-white face of Madame Vickers staring down at us, with Finch sneering behind her. The two of them were crafty as cats when they

31

wanted to be, taking great joy in sneaking up on children who were sitting in the garbage when they ought to be working.

"Give it to me!" repeated Madame Vickers.

Thomas looked as though he was going to make a run for it, and feeling as if it would be a very bad idea if he did, I lurched forward and tore the paper from his hands, holding it out to Madame Vickers.

[ILLUSTRATION: The symbol of the square and teardrop put together as one.]

32

"Not that, you fool!" She reached her pasty hand down toward us and pointed a long crooked finger at the ground. "That! Give me that!"

I looked at the ground and saw she was pointing to the saddlebag with the name Mingleton on it. Thomas grasped the strap and lifted the bag up toward Madame Vickers. She lurched forward with stunning quickness and seized it. Then she swung it back over her shoulder and belted me clean across the side of the head. The blow laid me flat out on the ground, and through the buzzing noise in my head I heard Finch's rapturous laughter. There was a smear of stinking mud on my cheek, which I tried to wipe away with the back of my hand as I stood up.

"Finchy!" cried Madame Vickers, holding the saddlebag out to him. "Take this and clean it up. It'll fetch a good price at the stables tomorrow." She pointed her awful finger at us again. "And you!"

Madame Vickers was positively outraged. Her eyes seemed about to jump clean out of their sockets and her hands were shaking with nervous energy. She could be very dramatic at times such as these.

"You two have been nothing but trouble since you came here!" she proclaimed. "Come to the thrashing post when the bell tolls. Count the desperate rings of the bell if you have the courage! That's how many lashings you can each expect!"

33

We thought she was through with us, but there was one last thought on her mind. "Give me the paper."

I looked at Thomas and he nodded, indicating that I should waste no time handing it over. Both of us were quite convinced that it would take only a moment's hesitation to turn Madame Vickers to violence once more.

Madame Vickers saw what was on the paper and laughed. "There's no hope you'll ever go there, no hope at all. I won't have you daydreaming about some stupid adventure far away from here. That will never happen!"

As she turned to go, the paper clutched in her hand, she said to Finch, "Next time bring the dogs and show these filthy boys no mercy."

She turned just one more time in our direction and yelled so loud her voice cracked like a whip on the wind. "Back to work!"

After we were sure they had gone far away, Thomas and I sat down next to each other. We pulled up our pant legs and examined our bare knees, something we'd done a thousand times before. My face felt like it was swollen to twice its normal size, and when I talked, the words came out like a slur.

"Did you see that, Thomas? Did you see what I saw?"

34

Thomas craned his head around and looked up at Madame Vickers's House on the Hill with a cool smile.

"Our time here has come to an end, brother. But we won't be leaving until the two of them know for certain how rude it is to hit a boy across the head with a saddlebag."

For once I was giddy with excitement at the thought of the tricks Thomas had cooked up to torment Finch and Madame Vickers.

I had a feeling the biggest trick of all was soon to come.

35

***

CHAPTER 4

OF KNEES AND MARKINGS

I don't think a person has really sat and listened to a very good story in the right way until they've done so with someone like Yipes, someone for whom the real world and the story being told switch places. It's the 'Warwick Beacon, the Lonely Sea, and the man before us who are the story, and the story of the two boys under the rule of Madame Vickers and Finch that is real -- so real that one feels the saddlebag against the side of the head, and flies into a rage at the injustice endured by two young brothers.

"That woman!" yelled Yipes. He was beside himself, shaking with anger. "That woman and her terrible son! And those dogs!"

It's hard not to enjoy it when your closest friend is carried away on the wings of a story, and both Roland and I began to laugh. This seemed to bring Yipes back to us, though a glimmer of the House on the Hill remained in his slightly narrowed eyes. He jumped to his feet and gathered the empty c

ups.

"I'll fetch one more cup of tea for the three of us and another loaf of bread." He started for the stove and then stopped short. "Will you show me your knees when I get back?"

36

Both Yipes and I held our breath, waiting to see what Roland would say. He made us wait, plying the wheel between his hands, and then he gave us a nod and a wink before Yipes darted off to fill the cups and get the bread.

When he returned, Yipes carefully set the cups on the deck and broke the bread into three pieces. He hunkered down with his cup of tea, blowing off the steam, and I noticed the wind had picked up just a little.

"We should draw down the smaller sail, the one at the very top," said Roland. "We're a bit fast for my taste today."

Yipes shivered from head to toe and his tiny mustache quivered back and forth at the thought of having to wait another second before returning to the story. It took all of his will to set the steaming cup down and stand back up, prepared to do the captain's bidding. He raced across the deck and scampered all the way up the mast until he reached a wooden perch where the topsail could be drawn down.

"Did you really need that little sail taken down?" I asked.

"No, not really," replied Roland. "But I can't help driving him mad at least twice a day. It keeps my spirits up."

Yipes slid down the mast and ran across the deck to rejoin us, careful to avoid the bread and the teacups as he sat back down. He picked up his tea and cradled it gently in his lap, staring intently at Roland's legs behind the wheel of the Warwick Beacon.

37

"Let's see those knees," he said, a twinkle of great expectation in his voice.

It appeared as though Roland thought about whether or not there was another silly errand he could send Yipes on before proceeding, but coming up with nothing very interesting, he decided it was as good a time as any to go on with his story. He stepped out from behind the wheel, locking it with a wooden pin as he came around, and knelt down in front of Yipes and me.

"That piece of paper, the one we found in the saddlebag," began Roland, looking intently at the two of us, "there was time enough for us to read it before Madame Vickers snatched it away."

"What did it say?" Yipes was about to keel over from anticipation, and the slightest pause from Roland sent him into a fit. "Out with it!"

Roland smiled and, standing just a little, began to roll up his pant legs until they were over his knobby knees. He was quite a burly man, and his legs were covered in a lightly colored mat of furry hair. Yipes and I both leaned in close so we could clearly see his knees.

There appeared to be a very old image directly above his kneecaps. It was dark brown -- like a birthmark -- but it was also perfect in its shape and form, as if it had been put there by someone. The markings were all of circles, interconnecting and darting back and forth between his knees. Roland touched his knees together and the two halves became one.

38

[ILLUSTRATION: The marking on Yipe's legs.]

"You've got an awful lot of hair. I can hardly see past it," said Yipes, intent on discovering all he could of the strange markings. He reached his hand down and tried to touch Roland's leg and Roland gave it a quick slap.

"No touching the captain's hairy legs. That's not allowed."

"But what does it mean?" cried Yipes. "All those circles, darting around as if they've got no home."

Roland pulled himself up to his full height and rolled down his pant legs, going back to the wheel. He pulled the wooden pin out and took control of the Warwick Beacon again.

"Thomas had markings on his legs as well," he said.

39

"Only his were all squares. If we sat across from each other when we were young, all the squares and all the circles became connected. We looked at it for years, trying to understand what the markings meant and from where they had come, but we could never figure it out."

Roland paused, taking one of his hands from the wheel and scratching at his ear.

"Until we found that piece of paper at Madame Vickers's House on the Hill."

Yipes and I looked at each other with wide eyes, feeling sure we were about to be let in on a fantastic secret. We watched as Roland took his logbook out of his pocket and opened it to a certain page. He handed the book over -- something he'd never done before -- and Yipes quickly reached out and snatched it away.

"Careful with that!" cried Roland. "If it goes overboard we won't know where we're going or how to get back."

Yipes was suddenly aware that he had in his hands a very important item that he didn't care to be responsible for. He thrust it into my hands and leaned in close, where the two of us spied a drawing on the left-hand page.

"As close as I can recall, that is a reproduction of the piece of paper we found in the Mingleton's saddlebag at the House on the Hill," said Roland, gazing off into the horizon.

Yipes and I looked carefully at the page, reading the words and spying the image of the square and the circle

40

put together. It was uncannily like the one we'd just seen on Roland's knee.

"If you want to know the meaning of those words and that image before the sun sets, we best get back to our story," said Roland. "Take up your bread and your tea and I'll tell you what happened that night at Madame Vickers's House on the Hill."

[ILLUSTRATION: A piece of paper that reads: WESTERN KINGDOM

WAKEFIELD HOUSE

FAILED!]

41

***

CHAPTER 5

The Toll of the Bell

For the rest of the day Finch kept the dogs on their long leashes and let them stray between the piles of trash. He set us all to picking through the same giant stretch of rubbish, where he could keep a watchful eye and sic Max and the Mooch on anyone who slacked off. There was nothing in the world like the thought of two very big, very mangy dogs tearing at your ankles to make a boy work faster.

Thomas and I whispered of a great many things as the day passed. We whispered of the symbol on our knees and how it had matched that of the image on the piece of paper from the saddlebag. We wondered aloud what the words on the piece of paper had meant -- Western Kingdom -- Wakefield House -- Miss Flannery -- FAILED! We wished we could have the paper back again, to try to find something else written there that might enlighten our search for answers. We also spent a good deal of time talking about the bell that would soon toll and how we needed to escape what was likely to be the beating of our lives. On this topic Thomas was the primary planner, having spent hours and hours thinking

42

about what he might do to Madame Vickers and Finch should we ever find a way to leave the House on the Hill for good.

"One thing is for sure," I said after some thought. "We simply have to go to the Western Kingdom, by whatever way possible, and seek out the Wakefield House and Miss Flannery."

On this point we agreed, and soon we were planning our escape in hopes of making our departure before the sound of the bell drifted over the hill of garbage. Throughout the morning, Thomas secretly darted back and forth between the younger children, calling in every favor he'd saved up for just such a time as this. Our stomachs rumbled as the noon hour approached and the dogs became excited as Madame Vickers strode down the winding path with two bags slung over her shoulder and a dirty old jug in her hand.

When she arrived, she stared boldly at the group of us and seemed to take some pleasure in tossing one of the bags in our general direction. The bag burst open when it hit the ground, revealing a block of moldy cheese and two loaves of hard, stale bread. Max and the Mooch bolted forward, yanking their leashes from Finch's hand, and pounced on the food. They began by tearing the cheese to pieces, making such an awful sound of growling and slobbering and chomping that not one of us had even a

43

tenth of the courage it would have taken to reach in and try our luck at grabbing something for ourselves. When all the cheese was gone, each of the dogs chomped down on a loaf of br

ead and, growling viciously in our direction for good measure, returned to lie down by Finch and eat the rest of our lunch.

"Next time you'll need to be quicker," Madame Vickers said with a sly grin, as though she'd been imagining the scene that had just taken place and was glad to find it playing" out as she'd hoped. "I suppose now you'll have to go without food until dinner."

She turned to Finch and handed him the other bag and the jug she'd carried down the hill. We all watched him open the bag and take out a fresh loaf of bread, a glorious-looking red apple, and slices of delectable-looking orange cheese. "Enjoy your lunch, Finchy. And do keep a close eye on that one." She pointed at Thomas. "Who knows what he'll try next!"

She started up the hill, then yelled back over her shoulder, "Give them the jug when you've had all you want. They'll work faster if they're not too thirsty."

Finch nodded and took a bite of the apple, savoring the crunchy sweetness. None of us moved as the dogs choked down the last of our bread and

44

Finch guzzled from the jug. When Madame Vickers had gone far enough up the hill that she could not hear Finch any longer, he looked us up and down where we stood and took another bite of the apple.

"Back to work with you!" he screamed, sputtering apple juice down his chin and wiping it with a grimy arm. "The next one of you fools to find something of real value gets the core of this apple. But it must be small enough to fit in my pocket. A ring or a coin will do just fine."

Eve of Destruction

Eve of Destruction Phantom File

Phantom File Ghost in the Machine

Ghost in the Machine The Land of Elyon #4: Stargazer

The Land of Elyon #4: Stargazer The Tenth City

The Tenth City The Dark Planet

The Dark Planet The Crossbones

The Crossbones Mr. Gedrick and Me

Mr. Gedrick and Me The Black Circle

The Black Circle Floors

Floors Beyond the Valley of Thorns

Beyond the Valley of Thorns Quake

Quake Tremor

Tremor Rivers of Fire

Rivers of Fire The House of Power

The House of Power Dark Eden

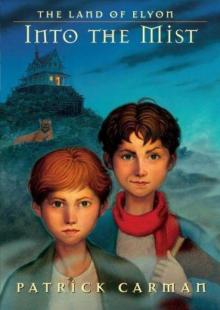

Dark Eden Into the Mist

Into the Mist Fizzopolis: The Trouble With Fuzzwonker Fizz

Fizzopolis: The Trouble With Fuzzwonker Fizz Pulse

Pulse 3 Below

3 Below The Dark Hills Divide

The Dark Hills Divide Skeleton Creek

Skeleton Creek The Raven

The Raven Thirteen Days to Midnight

Thirteen Days to Midnight Fizzopolis #2: Floozombies!

Fizzopolis #2: Floozombies! Rivers of Fire (Atherton, Book 2)

Rivers of Fire (Atherton, Book 2) Stargazer

Stargazer The Trouble with Fuzzwonker Fizz

The Trouble with Fuzzwonker Fizz Floors #3: The Field of Wacky Inventions

Floors #3: The Field of Wacky Inventions Floors #2: 3 Below

Floors #2: 3 Below Floors: Book 1

Floors: Book 1 Crossbones

Crossbones Floors:

Floors: Fizzopolis #2

Fizzopolis #2 The Black Circle - 39 Clues 05

The Black Circle - 39 Clues 05 Into The Mist (Land of Elyon)

Into The Mist (Land of Elyon)